How the Country Can Bring Peace to the Middle East

Table Of Content

In his recent speeches in Egypt and Israel, U.S. President Donald Trump repeatedly invoked the word “peace” when describing his vision for a new Middle East. He is right to do so. After decades of perpetual conflict, the region may be on the precipice of a genuinely stable future. As we argued in Foreign Affairs last December, Israel’s battlefield achievements against Hamas and Hezbollah—together with the collapse of Bashar al-Assad’s regime in Syria—had created a rare opening for the Jewish state, the United States, and key Arab countries to forge a coalition capable of stabilizing the region and countering extremism. And developments since then have only made that vision more urgent and attainable.

Earlier this month, after two years of fighting, Hamas and Israel finally agreed to a U.S.-brokered cease-fire that could both end the war in Gaza and dismantle the terror organization. Israel and the United States have decimated Iran’s network of proxies and struck the country’s own nuclear and missile infrastructure, breaking the Islamic Republic’s grip on much of the Middle East. As a result, these two regional spoilers are on the back foot. A better future, in other words, is very much within reach. Even Israeli politicians—foremost among them Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu—are speaking of peace again, after years in which that word had virtually disappeared from their lexicons.

That does not mean the path forward is obstacle-free. Israel is diplomatically isolated and extremely unpopular on Arab streets, in European squares, and on American campuses. Hamas is still the strongest political and military force in Gaza and has maintained support in the West Bank. Iran remains dangerous, even if it is weaker. And a radical Muslim Brotherhood, backed by Qatar and Turkey, is expanding its influence. Unlike in the past, these hurdles are all surmountable. But overcoming them will require a new regional coalition. This coalition will have to offer a moderate alternative to both the Iranian axis and Sunni jihadists. It will need to eventually expand into a broader Mediterranean partnership. And it must receive dedicated American backing.

ONCE IN A LIFETIME

Trump may have been disappointed not to receive the 2025 Nobel Peace Prize. But in the eyes of most Israelis, he has earned it. The U.S. president imposed a cease-fire framework on Netanyahu, who had resisted popular demand for a deal that would have returned all hostages and ended the war. Trump did so while simultaneously getting Egypt, Qatar, and Turkey to exert heavy pressure on Hamas, which had also been reticent to sign such an agreement. It was a display of diplomatic finesse reminiscent of the shuttle diplomacy U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger deployed to end the Yom Kippur War in the 1970s.

The agreement Trump brokered is opaque. Many of its provisions remain undefined, and it appears that Washington offered bilateral assurances—perhaps even contradictory ones—to both parties. But this ambiguity is deliberate, designed to allow each side to declare victory. Israel’s claim to victory centers on the return of all hostages, the military’s dismantlement of Hamas as an organized force, and the creation of an international plan to eradicate its rule and disarm its militias. Israelis also get to maintain a security zone in Gaza until Hamas’s disarmament is complete. Hamas, for its part, gets to declare that it withstood Israel’s army for two years, forced its withdrawal from Gaza, secured the release of thousands of Palestinian prisoners, put the Palestinian issue back on the global agenda, and extracted assurances that Israel will not resume the conflict.

The war in Gaza could reignite. Trump’s 20-point peace plan unfolds in three stages, and only the first is underway and well defined with numerical parameters: the release of all Israeli hostages in exchange for the liberation of convicted Palestinian militants, coupled with the redeployment of Israeli forces outside central Gaza. Hamas will likely exploit areas of ambiguity even in this stage to slow the transition to the next phase, as recent delays in the return of hostages’ bodies have demonstrated.

The second phase—disarming Hamas and establishing a new governing authority in Gaza with the participation of Arab and other international forces—will be far more difficult to implement. And should the parties fail to carry it out, Gaza could come to resemble Lebanon: formally ruled by a recognized government but effectively controlled by a militant organization. (Hezbollah has long dominated the Lebanese state.) In that case, Israel may once again find itself compelled to fight in Gaza wherever Hamas continues to operate.

Washington has achieved military success without the loss of a single American life.

Then there is the third phase. This stage calls for the creation of a pathway to Palestinian statehood and self-determination, conditioned on the full demilitarization of Gaza and sweeping reforms within the Palestinian Authority. It will be Israel’s most significant contribution to the Trump plan, taking place after Hamas’s dismantlement in the second phase. It will take far longer to see through, if it is even achievable.

Still, there is reason to be hopeful that this war, at least, is finished. Through a combination of pressure and inducements, Trump and his talented team have succeeded in forging an Arab-Palestinian front that supports the demilitarization of Hamas—an unprecedented achievement in a region where no actor has ever voluntarily surrendered its military capabilities.

The region’s broader conflicts might also simmer down, thanks to the weakening of the Iranian regime. Israel’s military campaign against Tehran severely damaged core components of its strategic apparatus, including its nuclear facilities, its missile systems, its air defenses, and, critically, its network of regional proxies. Israeli fighting in Lebanon, for instance, diminished the power of Hezbollah, which now faces mounting pressure from the United States and from Lebanon’s government. The Yemeni Houthis continue to pose a threat to the freedom of navigation in the Red Sea, but they are limited in their ability to hit Israel because of the country’s excellent air and missile defense. The survival and broad recognition of Ahmed al-Shara’s government in Syria further underscores Tehran’s diminishing influence, especially given that Shara clearly wants to prevent Iranian meddling in the country. Meanwhile, the Iranian regime is struggling to keep its own country’s economy running in the face of widespread sanctions. France, Germany, and the United Kingdom even recently reimposed the UN Security Council’s sanctions, using the snapback provisions in the 2015 nuclear deal.

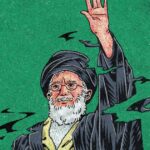

Still, the Iranian regime should never be underestimated, and it remains the Middle East’s most patient and determined threat. Its leadership seeks revenge against Israel, and it will almost certainly study the war’s lessons alongside its partners in Beijing, Moscow, and Pyongyang. Its nuclear infrastructure is bruised, but it has effectively dismantled the International Atomic Energy Agency’s oversight of its nuclear program and still has several nuclear weapons’ worth of enriched uranium on hand. It frequently threatens to alter its nuclear strategy and has hinted at leaving the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty or even obtaining a bomb. Iran is driven by a desire for vengeance against Israel and will use whatever weapons and cash it can scrounge up to proliferate and foster terrorism. It remains committed to perpetual conflict—which is why it is virtually the only government that did not welcome the end of the war in Gaza.

THE SPECIAL RELATIONSHIP

As it navigates a new future, Israel has a major advantage: its rock-solid relationship with Washington. For all the hand-wringing about the U.S.-Israeli alliance over the past two years, the two states coordinated more closely than ever after October 7, 2023. The results were excellent. The two countries’ attacks on Iran’s nuclear program, for instance, improved the United States’ leverage in future negotiations without prompting escalation or regional warfare: all the predictions that U.S. attacks would provoke a regional war, close the Strait of Hormuz, prompt oil prices to skyrocket, and yield a wave of terror never materialized. Meanwhile, in Gaza, American diplomatic, financial, and military support allowed Israel to degrade Hamas and thus strike a deal to bring the hostages home. That doesn’t mean the two sides were perfectly aligned; in private, U.S. officials pushed their Israeli counterparts to move toward peace, resulting in this month’s agreement. Yet Washington showed that genuine influence over Israeli policy derives not from public reprimands or arms embargoes but from unwavering public support and closed-door pressure.

As a result, for the first time in the twenty-first century, the United States has reasserted its leadership role in the Middle East. It has achieved military success without the loss of a single American life and facilitated a peace that has been broadly welcomed across the region. Washington has demonstrated that sustained and strategic involvement in the Middle East can, in fact, reinforce the United States’ position as a leading power—in contrast with its rivals. The region is not a quagmire of endless conflicts and financial burdens from which it must disengage.

But for Israel, relations with the United States are now the diplomatic exception. Almost everywhere else in the world, the country is facing a tsunami of condemnation. The harrowing images from Gaza have overshadowed the massacre of October 7. Distorted narratives—including claims that Israel deliberately starved civilians—were fueled by anti-Semitic networks and Hamas’s global propaganda machine and compounded by Israel’s own diplomatic shortcomings. This prompted recrimination from both the country’s longtime critics and even some of its partners, including Germany and Italy. The consequences of all this anger are real. Arab governments, for example, have put a stop to their efforts at normalizing relations with Israel because they are fearful of antagonizing their constituents. Regional officials are also worried that Israel is aiming not just for security but for regional hegemony through military dominance and territorial expansion. But Netanyahu himself has said that Israel has no designs on Gaza, Lebanon, or Syria. The voices in his coalition who have called for annexing the West Bank face resistance from both the Israeli public and the Trump administration. Yet unfair as this reputation may be, Israel is nonetheless seen as a state whose conduct is fundamentally at odds with liberal values and as an unreliable regional interlocutor.

Israel is also staring down new regional competitors. Iran may be weakened, but Muslim Brotherhood–aligned governments in Qatar and Turkey have gained influence. Both states have leveraged their personal rapport with Trump to expand their regional influence, and both now coordinate closely with Washington on Syria, increasing their foothold there. Qatar has also extended its reach into Lebanon. After Israel’s failed strike on Hamas leaders in Doha, Trump even compelled Netanyahu to apologize to Qatar. The White House then offered the country defense assurances that were reminiscent of NATO commitments.

Neither of these countries threatens Israel in the same way that Iran does—or to nearly the same extent. In fact, both played central roles in securing a cease-fire in Gaza, and they currently play a central role in keeping Iran weak. But they are not friendly to the Jewish state, either. Qatar, for example, continues to act as a patron of Hamas, and it amplifies anti-Israeli messaging via its Al Jazeera media network. Israel will thus need to carefully manage its relations with the two countries and push for a shift in their hostile policies, ideally in cooperation with Washington. Otherwise, they could fill the vacuum left by Tehran by propping up Sunni radicals from East Africa to the Middle East.

RIGHT PLACE, RIGHT TIME

For Israel, diplomatic isolation, Iran, and Sunni extremism will cause continued headaches. Yet overall, the Middle East is becoming more favorable for Israeli interests. There is now a genuine opportunity to end hostilities between Israel and both Lebanon and Syria—and even to slowly normalize relations with both countries. There is also a chance to outright expand the Abraham Accords into the broader Muslim world. Indonesia—the world’s largest Muslim-majority nation—represents a particularly significant opportunity. So does Somaliland, in the Horn of Africa, which seeks international recognition and occupies a strategically vital position in the struggle against the Houthis. If Azerbaijan, a long-standing Israeli partner, formally joins this regional force, it would strengthen its own relationship with the United States and reinforce stability across Central Asia. And a political change in Israel could further promote normalization discussions with Saudi Arabia and other Arab states.

Changes in geopolitics will also facilitate such talks. Today, countries across the world, including in the Middle East, are seeking more autonomy in their relationships, diversifying partnerships, and redefining their dependencies. They are more focused on acquiring advanced technology—which has become the currency of power—and maintaining stability. That means the Middle East’s future will be shaped by actors who possess the military power to defend themselves and their allies without constant American intervention; the economic capability to rebuild and stabilize destroyed areas, and the technological excellence needed to link the region’s economies to Asia and Europe—all while drawing on U.S. leadership when needed. And Israel, with its powerful military, strong tech industry, and ties to Washington, is the best partner most Arab states can find for running this gauntlet.

These countries can deepen their integration even without normalization. They could build a technological ecosystem that links the United States to the Gulf’s infrastructure, its energy resources, and Israel’s knowledge and innovation, for example, without doing so—and it would be far less politically sensitive. But either way, Arab governments will have to overcome their fears of angering their populations and plow ahead with regional integration.

The Middle East is becoming more favorable for Israeli interests.

Israel can simultaneously forge an even stronger relationship with Washington. The two countries should set up a new technological partnership, codified in a bilateral memorandum of understanding, predicated on equitable Israeli-American capital contributions across important tech sectors—including artificial intelligence, quantum computing, energy, and semiconductors. As part of this initiative, the United States should also extend defense assistance to Israel for the ensuing decade.

Most of all, the United States should help facilitate Israel’s integration with its Arab neighbors. That means, most obviously, pushing for normalization. But it also means that Washington should ensure Israel’s innovative tech ecosystem is connected to the Gulf’s and invigorating the India–Middle East–Europe Economic Corridor (better known as IMEC). To do so, Washington could name a czar specifically tasked with making this bloc of states more cohesive. The envoy would, in turn, help catalyze a technological ecosystem that bridges the Gulf’s infrastructure with India’s advanced services sector, both of which fit into the Trump administration’s plans to turn the Middle East into the world’s second most important tech hub, after the United States.

On the military front, the United States should set up a permanent security architecture that combines both Israeli and Gulf resources. It should establish a regional air defense apparatus controlled by the U.S. military’s Central Command (popularly known as CENTCOM). But Washington should also establish a broader permanent joint command structure that oversees the region’s maritime, cyber, and counterterrorism operations. This structure can feature Bahrain, Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and even Qatar—if it recalibrates its policies.

To further their cooperation, Israel, the United States, and the Arab states should expand their regional coalition into a broader Mediterranean partnership—a kind of pax Mediterranea—that promotes stability, prosperity, and technological progress across all its members. Israel and the United States should do so by convening a leadership summit featuring Arab partners as well as Cyprus, Greece, and Italy (with planned expansions to Azerbaijan, Germany, and India). There, these countries would collectively invest in joint defense procurement and military logistics; technology and energy, with a priority on innovations that can mitigate the effects of climate change and reduce food and water insecurity; and a joint financial institution. They would also figure out ways to support regional reconstruction and plan for how to respond to the many natural disasters that can afflict their shared region. The United States can invite Qatar and Turkey to participate in the coalition if they end their anti-Israeli policies, cease financing Hamas and other terrorist groups, and generally stop spewing propaganda.

PEACE THROUGH STRENGTH

A U.S.-backed Arab-Israeli coalition has long been the most viable path toward a stable Middle East. And today, it is more achievable than ever. The challenges—regional mistrust, a resurgent Muslim Brotherhood, and an Iran and a Hamas that are itching to act as spoilers—are real. But if the United States channels its renewed assertiveness and if local actors can align their power with purpose, the Middle East may finally move from perpetual crisis management into a sustainable order.

To achieve this vision, Washington and its regional partners do not need to solve the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. But they can certainly try to shift its trajectory in a more hopeful direction. To do so, these actors will need to embrace Trump’s framework for a peace committee, which conditions any Israeli concessions on genuine Palestinian reform. The Palestinian Authority (or any other Palestinian government) will need to dismantle terror networks and end Palestinian incitement in schools, religious institutions, and the international arena. Israel will need to receive the remaining hostages’ bodies and retain its security primacy in Gaza in order to prevent Hamas’s resurgence and ensure that whatever administration follows is effective, made up of both Palestinians and international technocrats.

But regional integration cannot hinge on the Palestinian issue. A veto from Ramallah would almost assuredly doom the rest of this project—and, with it, the region’s chance at long-term stability. It is instead time to prioritize peace through strength in its truest sense: not as a slogan, but as a strategy anchored in shared interests, credible deterrence, and the conviction that stability is best secured by those prepared to defend it.

Loading…